A former pupil of Corelli, Geminiani (1687-1762) had already published two sets of arrangements of his mentor's works in 1726 (Concertos after Corelli Op. 5, nos 1-6) and 1729 (Nos 7-12). Although it was to Geminiani's financial advantage to promote his connection with the much-admired master, it was also apparently an act of reverence, expanding interest in Corelli's music, and bringing to the professional concert platform works that had previously been restricted to chamber (often amateur) settings. The original sonatas are transformed into concertos by the addition of ripieno violins and an (occasionally) concertino viola, while the continuo part is adapted to the new context from Corelli's organo part. While some contemporary critics still preferred the "light original dress" of the originals, others — including the public — approved Geminiani's removing "some of the ancient Stiffness of Style" and giving the music "a more easy, free and flowing air."

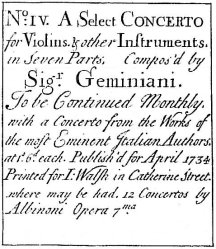

The 3 Concertos from "Select Harmony" followed the next year, as part of a series that included works by Vivaldi, Albinoni and "other Eminent Italian Authors". Hawkins, having heard the first of these concertos in concert, thought the second movement fugue "perhaps one of the finest compositions of the kind ever heard" (although he misremembered the mode and metre of the movement).

Thought to be among Geminiani's last publications, the 2 Unison Concertos are quite different to his other, mostly seven-part concertos, being this time only in two parts, both the first and second violins directed to perform from the upper, treble staff, and everyone else from the lower, bass staff. Whether Geminiani was satirising or supporting the "modern" galant idiom, often criticised for its lack of counterpoint and dependence on attractive melodic lines, is hard to determine; he most likely intended the concertos to demonstrate principals of composition outlined in his Guida Armonica (c1752), particularly the level of harmonic invention he believed necessary in music of all styles.

The concertos are further discussed in Christopher's Introduction and Critical Commentary to the edition, and illustrated with facsimiles from the original editions. Also included are a table of ornaments and an Appendix by Richard Maunder on the present state of research into performance numbers for concertos such as these. A practical edition, including parts, will follow shortly. Samples of the score may be viewed here.

Further volumes of Geminiani are expected in the coming months, including the six concertos of Op. 7 (edited by Richard Maunder) and the treatises The Art of Accompaniment (Peter Williams), The Rules for Playing in a True Taste Op. 8, A Treatise of Good Taste in the Art of Musick and The Art of Playing on the Violin Op. 9 (Peter Walls).