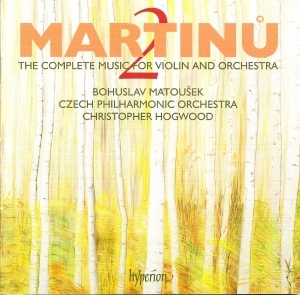

February

sees the release of Christopher's latest CD. This recording (Hyperion

67672) with Bohuslav Matousek, Karel Kosarek and the Czech Philharmonic

is the second in a four-volume series of Martinu's Complete Music for

violin and orchestra. Works featured on the CD are the Concerto da

Camera (H285), the Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra (H342) and

the Czech Rhapsody (H307A).

February

sees the release of Christopher's latest CD. This recording (Hyperion

67672) with Bohuslav Matousek, Karel Kosarek and the Czech Philharmonic

is the second in a four-volume series of Martinu's Complete Music for

violin and orchestra. Works featured on the CD are the Concerto da

Camera (H285), the Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra (H342) and

the Czech Rhapsody (H307A).

To buy your copy, please visit Hyperion Records

To read the sleeve notes click on the Read More button.

CD SLEEVE NOTES

reproduced with kind permission from Ales Brezina

ON 29 JANUARY 1941 the Swiss conductor Paul Sacher wrote to Bohuslav Martinu in Lisbon: ‘I am preparing the general programme for the 1941–2 season. I need a modern piece for violin and orchestra and would like to ask you if you would be willing to write a concerto of this kind. I am looking for a composition of some fifteen to twenty minutes that would be suitable for my leader Madame Gertrud Flügel. She is a violinist of tremendous technique, a very musical artist, who specializes in vigorous movements bursting with strength and momentum rather than in the elegant and witty genre. Nevertheless, her soft playing has an intimate charm. I don’t know if you remember her? The accompanying orchestra should be limited to just strings with a percussion and piano according to your choice.’

The commission for the Concerto da camera H285 for violin, piano, timpani, percussion and string orchestra arrived at a turning point in Martinu’s life. Since July 1940 he had been engaged in a highly dramatic escape from France, where he had lived for seventeen years and achieved a remarkable reputation, but which was now occupied by the German army. His emigration to the USA marked a radical change in Martinu’s lifestyle. On 6 April 1941, he referred to this in his letter to Sacher: ‘I arrived here [in New York] in a lamentable condition, […] but I have to work a lot since I don’t have enough of my music with me, and everybody asks me for scores which unfortunately remain in Europe, so I have to compose new pieces.’ But it proved to be more difficult than the composer expected. In his next letter to Paul Sacher (14 June 1941) he admits that even if he had ‘the firm intention to write the [proposed] concerto for violin’ he had not ‘taken into account the great change nor the reaction to all those recent events. I started to work but the result is not at all good; I have to admit that the new life here absorbs me too much, giving me no time to look after myself, and I am banking now on the summer to bring order to my mind.’

Indeed he didn’t start working again on the concerto before the middle of July while spending the summer in a small country house in Edgartown, Massachusetts. Here Martinu rediscovered the ‘order’ necessary for creative work, and even recovered his fine sense of humour, as seen in a letter to his friend Rudolf Firkusny (12 July 1941): ‘There is quite an acceptable piano here which works in accordance with the weather—whenever it is nice weather, it works, but during that time I am on the beach. When it is rainy and wet, it does not work at all.’ This was of course an exaggeration typical of the composer, as became clear from his letter to Sacher written just ten days later: ‘I finished the first movement and am close to finishing the second as well; everything should be ready within fifteen days […] I believe you will be pleased with the piece.’

After Martinu completed the concerto, which he dedicated ‘to Paul Sacher and his Basel Chamber Orchestra’, he made another copy for safety reasons and through the Swiss ambassador in the USA he sent it on 20 August to Basel. As early as 9 September Sacher telegrammed back: ‘Score arrived, am enthusiastic about the piece.’

In the Concerto da camera Martinu returned once more to his favourite concerto grosso form, which allowed him to avoid the thematic dualism of sonata form and to concentrate on the constant evolution of small musical cells. The first movement, Moderato, poco allegro, is in variation form, with spicy harmonies that are quite often polytonal. The orchestral writing is transparent and clear with only spare use of the timpani. The second movement, Adagio, is reminiscent of a baroque aria, characterized by the highly dense polyphonic writing for the string orchestra. It anticipates Martinu’s development towards emotional warmth and a Dvorák-like cantabile quality. The piano part, with its long rhythmical values, constitutes a sort of cantus firmus under the rich figurative work of the orchestra and the solo violin. The third movement, Poco allegro, is a rondo with a melodically and rhythmically distinct motif related to that of the first movement. The orchestra is given added colour by cymbals and a triangle. Martinu again combines elements of concerto grosso with lyrical cantilena close to the expressive world of Dvorák.

The premiere of Concerto da camera took place on 23 January 1942 in Basel with Gertrud Flügel and the Basel Chamber Orchestra under Paul Sacher. Three days later Sacher telegrammed to Martinu: ‘Violin concerto accepted with enthusiasm we all thank you.’ Because of the freshness of its musical invention, the sensual sound of the orchestral part and the virtuosity of the solo parts, the Concerto da camera is a favourite among Martinu’s instrumental concertos; it provides delight to both performers and listeners.

It was unknown until recently that Martinu later slightly simplified the solo violin part, probably as a result of suggestions from the American violinist Louis Kaufman, who describes it in his memoirs A Fiddler’s Tale. This version of the concerto was published by Universal Edition in Vienna, and is recorded here. The planned complete critical edition of the works of Bohuslav Martinu will include both versions of the work.

During the 1940s, Martinu composed at least one new work for the violin every year: the Concerto da camera of 1941 was followed in 1942 by the Madrigal Sonata for flute, violin and piano, and a year later by the Violin Concerto No 2. The Czech Rhapsody H307A was written at Cape Cod, South Orleans, Massachusetts, from 5 to 19 July 1945. In a letter from 10 July Martinu remarks to Milos Safránek: ‘… it is a form I thought I would no longer write in, and I am finding it rather difficult.’ This virtuosic composition, originally for violin and piano, was commissioned by the celebrated violinist Fritz Kreisler and is dedicated to him. As far as we know Kreisler never performed the piece. In fact it is difficult to imagine Kreisler, who by that time had reached the age of seventy, reckoning with the exceptionally difficult technical demands of this piece, which include double stops at the interval of a tenth as well as rapid runs and large intervallic leaps. The central key of the Czech Rhapsody is B flat major, which appears in Martinu’s later works as a symbol of hope and happiness, which would fit into the atmosphere of the end of World War 2. It should be noted that another composition by Martinu also bears the title Czech Rhapsody: a cantata for baritone, chorus, orchestra and organ dating from 1918, also composed in the throes of a world war, dedicated to the Czech writer Alois Jirásek.

Martinu had originally intended to write this work for violin with orchestral accompaniment. He wrote to his friend Frank Rybka (on 24 June 1945): ‘For Kreisler I’ve written a Czech Rhapsody, for the time being with piano.’ To a certain extent, then, the existing piano part was really conceived as a piano reduction, which Martinu then intended to orchestrate. With this in mind, the Martinu Foundation commissioned the composer Jirí Teml to orchestrate the work, which he did with the help of the violinist Ivan Straus. Teml’s point of reference for the orchestration was the stylistically similar Rhapsody concerto for viola and orchestra, H337, composed in the spring of 1952. The details of the premier of the original version for violin and piano have not yet been tracked down; the orchestral version on this disc was heard for the first time at the Martinu Festival in Prague in December 2001.

Although written for the same set of solo instruments as the Concerto da camera, the Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra H342 represents a completely different approach towards this medium. It was composed in New York from 1 December 1952 to 10 March 1953, four years after the communist takeover in Czechoslovakia, which prevented Martinu returning to his native country. This enigmatic and highly personal work, structurally driven by its emotional nature, probably echoes the crisis in the composer’s personal life, caused by the sudden breakdown in the summer of 1952 of his long-term relationship with Rosalyn Barstow. We can, however, follow the progression of the work through the correspondence of the composer with Olga Schneeberger, an Italian friend. On 21 October 1952 he mentions to her ‘a well-paid commission for a concerto for violin, piano and orchestra’. According to his letter of 8 December (his birthday) he had finally started to compose the concerto: ‘After a week of contemplation on the subject I now feel in the right condition to do it.’ On 17 January 1953 he remarks that ‘the concerto develops well; I have already received the first bank check for it’. After a break caused by the preparatory work for the television premiere of his new opera The Marriage on the NBC, he writes on 9 February: ‘I have to return to this concerto, which I have neglected for a while.’ A month later the piece was finished.

Compared to the rather neo-Impressionistic works from this period—the most prominent one being the complex and dense Phantaisies symphoniques (Symphony No 6, H343)—the Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra appears to be surprisingly tonal and traditional. Its first movement, Poco allegro, combines neo-baroque techniques with elements of jazz. The toccata-like opening in D minor evokes the famous Double concerto for two string orchestras from 1938, and introduces a feverish ostinato around the basic note D. This is followed by a surprisingly Dvorák-like melody in the strings. The first entrance of the solo piano adopts the toccata of the orchestral introduction, but in E flat minor. The solo violin steps in, taking up the string melody of the introduction, now in E flat major. Throughout the middle section Martinu works with these two motifs. After the recapitulation a coda in E major closes the movement.

The second movement, Adagio, opens in a sort of E minor. Though very tonal again, here the proximity to his more typical music of that time such as The Greek Passioncan be felt, distinguished by sudden changes of mood as well as of the density of orchestral texture. It feels like a strange meditation, anticipating with its simplicity Martinu’s elementary folk cantata Opening of the Springs from 1955.

The solo violin enters with a variant of its theme from the first movement. The piano joins in with figurative passagework in C major, at first providing an accompanimental backdrop for an orchestral oboe solo and only gradually developing into a genuine solo part. A richly figurative cadenza for the two solo instruments is followed by a vibrant orchestral melody that reminds us of the composer’s Czech origins. Here, for the first time, the typical Juliette chord progression appears, a sort of plagal cadence best known from his opera Juliette which also appears in several other works, especially from the 1950s. The movement closes in an emphatic C major.

The opening orchestral section of the Allegro reflects the world of Martinu’s Symphony No 4, written at the end of World War 2. The piano enters in C major with an optimistic variant of the toccata-like figuration of the first movement. Just two bars later it is joined by the solo violin. The second theme sounds like a highly unusual fusion of the expressive worlds of Dvorák’s violin concerto and late nineteenth-century Italian opera. Short melodic cells, however, refer to the neo-baroque period of Martinu. What seems at first to be a literal reprise is suddenly stopped after just thirteen bars by a highly operatic procedure: a long pause followed by an unusually dramatic, even tragic, entrance of the piano. It is easy to see at this point a sort of Faustian dilemma (‘Two souls live in my chest’), but we cannot know whether this was what Martinu had in mind. The dark vision is lightened slightly by the entrance of two clarinets and by a gradual tonal stabilization. Step by step the orchestra comes in. The coda is in Martinu’s favourite key of B flat major; it presents stretto fanfares from the oboes and trumpets and modulates to E minor. A chorale melody finally leads to the culmination in C major.

The premiere of the Concerto for violin, piano and orchestra took place on 13 November 1954 in San Antonio, performed by the concerto’s dedicatees, Benno and Sylvia Rabinof (violin and piano respectively), with the San Antonio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Victor Alessandro. Its success led to several further performances, and on 27 March 1957 the Rabinofs wrote to the composer: ‘Your concerto becomes nobler and better-loved every time we play it.’

ALES BREZINA © 2008