Volume one of the complete keyboard works of Hardenack Otto Conrad Zinck was reviewed in Clavichord International, 15. no. 1 (May 2011), and the remaining two

volumes are now available.

Volume one of the complete keyboard works of Hardenack Otto Conrad Zinck was reviewed in Clavichord International, 15. no. 1 (May 2011), and the remaining two

volumes are now available.

Volume 2 contains a further six sonatas, the first four of which appeared in print between 1791 and 1793 in the four volumes of Compositioner for Sangen og Claveret. In general, they exhibit less of the Empfindsamkeit of the sonatas in the first volume (although the slow movement of Sonata 8 is a highly passionate work recalling Zinck's teacher, C.P.E. Bach) and a greater assimilation of Haydnesque figures. There are still plenty of notable moments, including the first movement of Sonata 7, which is built entirely on dotted or triplet figures, and the central section of that Sonata's final rondo-like movement, in which a syncopated figure in octaves covers some 60 bars. Sonata 8, in G minor, offers far greater originality verging on the eccentric in its modulations, figurations, and textural and tempo changes in the first movement; indeed, there is a passage of arpeggiated triads in sixteenth-note triplets that could be the eighteenth-century counterpart to the well-known closing passage of Rossi's Toccata 7! The closing Presto also makes forays into extraneous keys, its mainly two-voiced texture being interrupted by full chords in the left hand. The first movement of Sonata 9 is a moto perpetuo with little respite, while the slow movement carries the comment that if the composer had had a good mood and more time, he would have composed further and better variations to go with the one printed. The closing Rondo is short - its eighth-note movement is not as taxing as other pieces in this collection. The first movement of Sonata 10 is close to Koželuch, and alternates allegro figuration with a cantabile, Italianate second subject. Its slow movement also offers contrasts, the central section consisting of sixteenth-note figuration over quarter notes. The closing Poco a poco presto in 3/8 offers sufficient rhythmic and articulation challenges, and requires a top G.

The remaining two sonatas are taken from a manuscript collection compiled by Zinck's brother, Bendix, and are in general considerably less demanding. The first one opens with an andante, followed by a short Romanze marked lanto, and closes with an Andantino con [8] variazioni with increasingly lively figuration through to No. 5 and closing with a Presto al'lnglese. The opening movement of the second sonata from this MS is built almost entirely on Alberti bass figuration below a cantabile line; one wonders what his teacher would have said! There follows a Grazioso in similar style, and the sonata closes with a Rondo that is full of tuneful charm, although it is trickier than it appears.

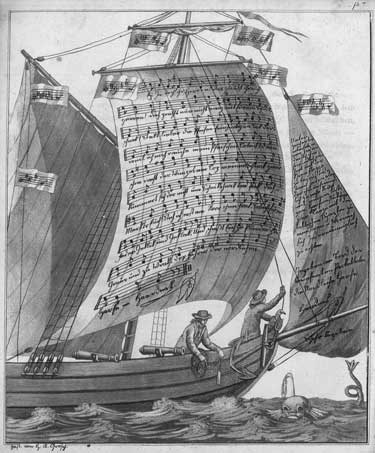

Volume 3 includes two sets of variations and some twelve short, miscellaneous pieces, including an untitled piece marked as a "stop-gap" taken from Compositioner that is in the style of a polonaise. From the manuscript compiled by his brother there are three minuets, a polonaise, an Adagio, an Allegretto, and a Rondo. There are also three Solfeggii (one being in two versions); one is a simple binary-form piece mainly in quarter notes, the other two have brilliant right-hand passagework. The other piece is a setting of the song "Das Traumschiff," its flowing melodic line over sixteenth notes approaching Schubert, or even the Lieder ohne Worte of Mendelssohn. The reproduction of the melody and text written onto a ship's sails is fascinating. Most of these pieces are carefully fingered. The sets of variations comprise seven on the popular song "Lison dormait," taken from the Compositioner collection and specifically directed by the composer towards the younger player. These increase in brilliance, but only the crossed hands passages in No. 5 pose any real problem. The expansive set of twenty-four variations on the "Rundgesang der Kinder in Ludwigslust" was published separately in 1787, and its origins are described in the Introduction. Suffice it to say that its striking technical demands in the later variations, including an extensive cadenza, will exercise even professional players.

This new edition faithfully carries across the fingering, phrasing and highly detailed articulation markings that make these pieces so suitable for the clavichord. Volume 2 is ring-bound with a wrap-around cover, while Volume 3, being shorter, is stapled (the pages remain open without any problems). Christopher Hogwood deserves our thanks for disinterring these pieces, in particular the sonatas, and especially the quirkily original No. 8 in Volume 2, from the mausoleum of the lesser-known composers. It is for us to bring them to life beneath our fingers and introduce them to a fresh audience.

— John Collins, Clavichord International, Volume 15, No. 2, November 2011