Christopher’s

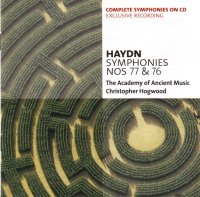

recording of Haydn’s symphonies 76 and 77 with The Academy of Ancient

Music was the cover disk with the May 2005 issue of BBC Music Magazine.

Christopher’s

recording of Haydn’s symphonies 76 and 77 with The Academy of Ancient

Music was the cover disk with the May 2005 issue of BBC Music Magazine.

Writing in BBC Music Magazine, Richard Wigmore introduces these two delightful, witty symphonies, commissioned in 1782 and intended for performance in London.

TRACK LISTING

Symphony no. 77 in b flat

1. Vivace 8:50

2. Andante sostenuto 5:37

3. Menuetto (Allegro) 2:42

4. Finale (Allegro spiritoso) 5:50

Symphony no. 76 in e flat

1. Allegro 8:42

2. Adagio, ma non troppo 7:58

3. Menuet (Allegretto) 3:35

4. Finale (Allegro, ma non troppo) 8:01

Total CD duration 51:19

The composer

Haydn’s reputation has fluctuated more, perhaps, than that of any other great composer. Before his London visits in the 1790s he was acclaimed throughout Europe. Following his death in 1809, his music came to seem tame to a century that exalted the confessional and the apocalyptic and he lagged behind Mozart and Beethoven.

One problem is the lack of Shaffer Amadeus-type romanticism in his biography. The son of a master-wheelwright, trained as a choirboy at St Stephen’s Cathedral in Vienna, Haydn was engaged by Prince Paul Anton Esterházy in 1761 and served the family for the rest of his life.

In Haydn’s lifetime his music supremely represented moral and emotional depth. His great symphonies and quartets are among the marvels of civilised art, breathtaking in their expressive range and endlessly unpredictable in their structure. In our fractured age he has a power to uplift the spirit.

The works

Nowhere was Haydn’s music more popular than in London, where one newspaper even proposed that the composer should be kidnapped and ‘transplanted’ to England.

The Earl of Abingdon had attempted to secure Haydn for his 1782–3 London concert season, announcing: ‘The Shakespeare of musical composition is hourly expected’. Though the visit never materialised — doubtless because Prince Nicolaus Esterházy was reluctant to grant his Kapellmeister leave — its legacy is the set of three symphonies of 1782, Nos 76–78, intended for London. In a letter to the Paris publisher Boyer, Haydn advertised them as ‘beautiful, elegant and by no means over-lengthy... they are all very easy, and without too much concertante [i.e. soloistic passages for wind] for the English gentlemen’. Perhaps, for Haydn, the unusually suave surface of the trilogy’s two major-keyed symphonies, No. 76 and No. 77, represents a conscious attempt to woo the London public.

But in essence they continue the trend of Haydn’s music of the late 1770s and early 1780s (especially the Op. 33 quartets), combining an easy tunefulness with a wonderfully subtle, sophisticated craftsmanship — a fusion of ‘popular’ and ‘learned’ styles that reached its apogee in the 12 great London symphonies.

Symphony No. 77

Vivace

The innocent opening, with its whiff of opera buffa, is deceptive: this

is a closely argued movement, full of Haydn’s nonchalant contrapuntal

mastery. There is a contrasting lyrical second theme, lightly scored for

three-part strings shadowed by a bassoon. The development (2:57)

‘worries’ the opening theme in a series of modulating imitations, and

then tightens the screws in a passage of even closer canonic imitation.

After a pause, the second theme ushers the music back to the home key

for the recapitulation. Apart from the omission of the initial piano

statement of the main theme, this remains regular until Haydn opens up

surprising new vistas with a whimsical expansion of the second theme

(from 4:48).

Andante sostenuto

This lovely movement, part rondo, part variations, evolves freely from

the gracefully ornamented opening theme. The scoring, with muted violins

and delicate woodwind colouring, has a chamber-music sensitivity; and

as in the opening movement, Haydn uses the device of canonic imitation

to intensify the music’s expression.

Menuetto (allegro)

Refined sentiment is summarily banished in the fast-paced minuet. With

its stomping rhythms, offbeat accents and comic touches like the

‘fortissimo fart’ at the start, this is more like a lusty German dance

than an aristocratic one. The Trio is a lolloping Ländler, with a

folk-style melody over an ‘oompah’ accompaniment.

Finale (allegro spiritoso)

While the catchy opening tune suggests a rondo, the movement turns out

to be in clear sonata form, with everything growing from the contour and

rhythm of the fertile opening phrase. At the centre is a tense,

brilliant contrapuntal tour de force (2:48) that caps even the first

movement’s canonic development. But Haydn has further surprises up his

sleeve in the coda where, in a rare moment of ‘concertante’, woodwind

and horns give out a blunt, countrified version of the ubiquitous theme.

Symphony No. 76

Allegro

In typical galant style, the first subject alternates a vigorous call to

attention and a gracious descending phrase in dotted rhythm; both

elements are resourcefully developed. In the exposition the elegantly

contoured second subject (1:14) grows from an apparently incidental

phrase heard earlier (0:34). The development (3:35), varying and

dissecting the two main themes through a wide spectrum of keys, contains

one quietly audacious harmonic stroke. The recapitulation condenses

much of the exposition to allow room for a new development of the first

theme’s answering phrase.

Adagio, ma non troppo

Like No. 77’s Andante, this is an amalgam of variations and rondo.

Here, though, the structure is more clear-cut: a delicate, almost dainty

B flat string melody, increasingly embellished on its later

appearances, alternates with two minor-keyed episodes. The first, in B

flat minor (1:31), is haunting both in its instrumental colouring and

its dusky, Schubertian modulations. In sharp contrast, the G minor

second episode (4:46), with its pounding staccatos and volleys of

demisemiquavers, prefigures the G minor storms in the Andantes of the

‘Clock’ and ‘London’ symphonies. After the final appearance of the main

theme, with a telling new harmonic twist (6:40), a quasi-cadenza recalls

the turbulent figuration of the second episode.

Menuet (allegretto)

This is a more leisurely, courtly affair than the boisterous minuet of

No. 77, though Haydn injects a moment of drama when the cadence of the

first section is immediately repeated fortissimo in F minor. The Trio is

another rustic Ländler, deliciously scored for flute, violins and

bassoon in octaves, with the horns joining in where they can.

Finale (allegro, ma non troppo)

Continuing the urbane spirit of the whole symphony, Haydn writes a

leisurely paced finale, built on a single theme of almost finicky

elegance. The development (2:57) reveals the theme’s unsuspected

strength in a sequence of imitations. As in the finale of No. 77, the

coda (4:55) gives the unaccompanied woodwind a moment of glory in a

series of tootling, Papageno-ish exchanges.

CD key moments

A track-by-track guide to Haydn’s Symphonies Nos 77 and 76

Symphony No. 77

First movement (Track 1)

Haydn’s transition to the recapitulation has a ‘Mozartian’ smoothness

and poise. The development’s strenuous canonic imitations are cut short

by a Haydn-esque pause. The second theme reappears in a remote G major

(3:35). Second violins start to repeat the theme in G minor (3:44),

initiating a sequence of imitations that ease the music back to B flat

and recapitulation (3:57).

Second movement (Track 2)

The expressive climax in a movement that transforms galanterie into pure

enchantment begins at 2:53. The opening phrase is intensified in a

ravishing series of overlapping imitations, with flute, oboes and

bassoon adding delicate washes of colour to the string lines. Even

subtler is the moment shortly afterwards (3:39) where the ‘stray’ G flat

at the end of the theme’s first half prompts a breathtaking dip from

the tonic, F, to D flat.

Symphony No. 76

First movement (Track 5)

This symphony cultivates an air of genial sophistication, untroubled by

darker emotions or knotty compositional ‘problems’. There are moments

for the connoisseur in the harmonic sleight-of-hand in the development

(from 4:10). The music settles on the brink of D flat, and then the rug

is pulled from the listener as the music pivots to E flat.

Fourth movement (Track 8)

As in No. 77’s first movement, Haydn makes something special of the

moment of recapitulation. But here the means are different. The

development’s forceful climax leads to a pause; then the tripping theme

begins in its original texture but in the ‘wrong’ key of C minor (3:53),

stops in its tracks, and, with no harmonic preparation, resumes in the

proper key of E flat.