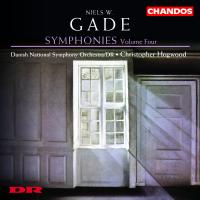

Symphony No.1 Op.5 ‘Paa Sjølunds fagre Sletter’

Symphony No.1 Op.5 ‘Paa Sjølunds fagre Sletter’

Symphony No. 5 Op.25

Ronald Brautigam piano

Danish National Radio Symphony Orchestra/ Christopher Hogwood

All works performed from The Niels W. Gade Edition

Chandos CHAN 10026

We reproduce the CD liner notes with kind permission from Chandos:

Niels Wilhelm Gade’s series of eight symphonies established an influential pattern for subsequent generations of Scandinavian composers, blending essentially classical form and Romantic expression, in the tradition of Spohr, Mendelssohn and Schumann, but adding to the mix a hint of Nordic folk music. The most radical of the series in many respects is his Symphony No.1 in C minor Op.5, composed in the spring and summer of 1842, when he was twenty-five. He intended it to build on the success of his overture Echoes of Ossian in a concert of the Copenhagen Musical Society the previous year. But when he submitted the new work to the Society in August 1842, it failed to win approval. Instead, he offered it to the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, where it attracted the attention of the orchestra’s director Felix Mendelssohn. After rehearsing the Symphony, Mendelssohn wrote effusively to Gade, saying that ‘not for a long time has any piece struck me as more lively or more beautiful’; and after the first performance in March 1843, he reported that it had aroused ‘the lively, undivided joy of the whole audience, which broke into the loudest applause after each of the four movements’. Gade travelled to Leipzig later that year, and in October himself conducted a second performance of the Symphony, with similar success. This led to an invitation to him to become assistant conductor of the Gewandhaus Orchestra, and for a short period after Mendelssohn’s death in 1847 chief conductor.

In a recent study, The early works of Niels W. Gade: in search of the poetic, the American scholar Anna Harwell Celenza has traced the origins of the First Symphony to an entry in a composition diary kept by Gade outlining the programme of a symphony ‘based on battle-text songs’, with only a few annotations of key and scoring, but with several quotations from the texts of Danish folk ballads. When Gade came to write the work, he apparently discarded several of these references; but he added a musical quotation, of his own 1840 setting of a ballad text by his older contemporary B. S. Ingemann, entitled Kong Valdemars Jagt (‘King Waldemar’s Hunt’), and beginning ‘Paa Sjølands fagre Sletter’ (‘On Zealand’s fair plains’). Gade’s song is heard in the slow introduction to the first movement of the symphony, and recurs later in the movement in different versions; it also returns in the finale. In addition, many of the other principal ideas of the symphony may well be derived, consciously or unconsciously, from its simple opening phrase, its later descending scale, its suggestions of hunting horns in the accompaniment, or its shifts between the minor key and its relative major. With hindsight, this intensive use of a song with folk-like characteristics on a Danish subject has been seen as giving the work a nationalist flavour. But Celenza argues that such a view is ‘the consequence of nineteenth-century German criticism and twentieth-century scholarship’, and has little or nothing to do with Gade’s intentions or how the symphony was perceived at the time; she even points out that the reason given by the Copenhagen Musical Society for turning down the work was that it was ‘too German’.

Ingemann’s poem ‘King Waldemar’s Hunt’ — derived from the legends which formed the basis for Schoenberg’s Gurrelieder and César Franck’s tone-poem Le chasseur maudit — relates how, as a punishment for blasphemy, King Waldemar is condemned after his death to ride every night with his followers on a wild hunt. The slow introduction to the first movement sets the peaceful scene described in the first stanza of the poem, with Gade’s song melody accompanied by quiet horn calls; then in the main Allegro energico the wild hunt begins. After the forceful first subject, which gains in impetus from its use of a dotted rhythm not as an upbeat figure but on strong downbeats, the song theme provides all the subsidiary material — notably a second subject of repeated horn fanfares, sounding first distant and then close at hand. Most unusually, the whole of the central development section reverts to the 6/4 time of the introduction and its mood of suspenseful calm. After a recapitulation which is a much altered version of the exposition, the movement has a coda based once more on the song theme, and ending in a triumphant C major.

Celenza relates the Scherzo of the symphony to the Danish folk ballad Elverskud, of which several lines are quoted in Gade’s composition diary (and which he was to use in 1853 as the basis for a large-scale cantata). The ballad describes a confrontation between Herr Olaf, riding into the countryside before his wedding, and the Elf-King’s daughter, who tries to attract him into her fairy world; when Olaf resists, she utters a curse on him, and he falls ill and dies, to be reunited with his bride only after her death from a broken heart. This programme would certainly explain the unusual construction of the movement, which, rather than having a conventional scherzo-and-trio outline, alternates between episodes in C major, with recurring crescendos in galloping rhythms suggesting Herr Olaf’s ride, and slower interludes in A minor, with muted violins over held chords conjuring up a fairy atmosphere. Each section is freely developed rather than repeated literally, with the third and final A minor interlude sadly recalling a theme from the C major sections, and the last C major section ending explosively.

This Scherzo is scored without the piccolo, trumpets, timpani and tuba of the outer movements of the symphony, but retains their quartet of horns and trio of trombones. The lyrical F major slow movement additionally drops the trombones, deploying the remaining instruments in Gade’s habitual changing mixtures of wind and string tone. Although no literary basis has been firmly identified for this movement, it does have a hint of narrative in its free alternation of its various themes, including a solemn horn melody, within an overall plan of two asymmetrical halves with extra rondo-like returns of the expressive first theme. In the C major finale, the exuberant opening idea is complemented by a solemn wind chorale, and by a folk-like melody accompanied by pizzicato strings, recalling the ‘bardic’ harp of Echoes of Ossian. These themes are combined in the largely contrapuntal development section with the song melody from the first movement; and the same melody recurs in the coda in a starkly simplified form, before being finally reduced to a succession of blazing fanfares.

Gade wrote his Symphony No.5 in D minor Op.25 ten years after No.1, in 1852 — by which time he had returned from Leipzig to Copenhagen, taken over the direction of the Musical Society, and established himself as a leading figure in Danish musical life. He conducted the first performance of the work at a Musical Society concert in December 1852. It was composed as a surprise wedding present to his wife Sophie, the daughter of his colleague J. P. E. Hartmann, whom he had married that April (and who was to die in childbirth in 1855). The surprise lay in the fact that it included an important piano part in all four movements. This was the first such keyboard obbligato in any symphony: but earlier the same year Gade had composed a Spring Fantasia for voices and orchestra which placed the piano in a similar role; and he may have found a model in Henry Litolff’s series of Concertos symphoniques for piano and orchestra, which had begun in the1840s. Gade’s piano part, reminiscent of Mendelssohn’s chamber music in the fluency of its figuration, is neither a concertante solo part, nor simply an intermittent accompaniment, but is as it were inlaid into the texture. Because such an effect is difficult to achieve on a modern concert grand piano, this recording uses a much lighter instrument made by Erard of Paris in 1837, with the orchestral strings reduced in numbers for the sake of balance.

Despite the happy circumstances in which it was composed, the Symphony begins (like No.1 and no fewer than three of Gade’s other symphonies) with a movement in the minor mode. Dramatic orchestral passages in dotted and double-dotted rhythms alternate with the two main themes, the first an expressive eight-bar idea accompanied by piano arpeggios, the second a major-key melody shared by the piano and the orchestra, with ingenious doublings, which is expanded to considerable length. After a repeat of this exposition section, the development is concerned less with discussion of themes than with movement through different keys and a gradual build-up in the weight of the piano figuration. In the recapitulation, the second theme first of all returns in D minor, but then shifts into the major; and the coda is also in D major, bringing back the first subject at half speed, and ending in tranquillity.

Of the two middle movements, the slow movement this time comes first. It is in the unexpected key of F sharp major, and in a gentle 9/8 time, with muted violins. The piano is silent throughout the calm first section, but joins in for the more dramatic middle section, and remains part of the texture, with continuous tremolandos and trills, in the much varied reprise of the opening. The Scherzo, too, favours variation over literal repeats, alternating in a continuous, developing sequence between three main sections in B flat major and two trios respectively in G flat major (a respelling of the slow movement’s F sharp) and E flat major. The piano writing here is at its most scintillating.

The D major finale, which adds piccolo and three trombones to the orchestral forces, begins with a slow introduction which, with its sustained horn note and solemn rolled piano chords, momentarily suggests a hidden programme similar to those underlying parts at least of the First Symphony. But the atmosphere of this introduction is dispelled in the ebullient main Allegro, with its first theme based on arpeggio figures and its second on graceful melodic curves; and although a few shadows pass across the development section, the work ends in a mood of joyful celebration.

© 2002 Anthony Burton